How To Setup Dependency Injection With Azure Functions ⚡

Learn how to set up Dependency Injection in Azure Functions using .NET .

Table of Contents

Dependency Injection (DI) is a technique to achieve Inversion of Control (also known as IoC) between classes and their dependencies.

Azure Functions supports Dependency Injection pattern.

With DI, you can segregate responsibilities into different classes and inject them into your main Function class. DI helps write loosely coupled code and improved maintainability, testability, and reusability.

If you are new to building Azure Functions, check out my Azure Functions ⚡ For The .NET Developer post to quickly get started. I’ll continue using the sample Function I used there and extend it to support Dependency Injection.

Setting Up Azure Function Dependency Injection

The Azure Functions we wrote earlier logs to the console. Say we want to do some business-related processing every time we get a message in the queue.

Let’s add a new class, MessageProcessor, to process this message. It implements the IMessageProcessor interface, which has the Process function that takes in the string message and does some processing.

The implementation currently checks if the message contains ‘exception’ and throws a code exception. This might do more valuable and relevant business checks and processes in your real-world applications.

public interface IMessageProcessor

{

void Process(string message);

}

public class MessageProcessor : IMessageProcessor

{

public void Process(string message)

{

if (message.Contains("exception"))

throw new Exception("Exception found in message");

}

}

The default Function class created by the Visual Studio template (in the previous example) is a static method in a static class.

To support Dependency Injection via the constructor, we need the class to be instantiated with a constructor. So let’s update the Function1 from the previous example to be non-static. Let’s also update the name of the class to be ProcessWeatherDataFunction.

public class ProcessWeatherDataFunction

{

private readonly IMessageProcessor messageProcessor;

public ProcessWeatherDataFunction(IMessageProcessor messageProcessor)

{

this.messageProcessor = messageProcessor;

}

[FunctionName("ProcessWeatherData")]

public void Run(

[QueueTrigger("add-weatherdata", Connection = "WeatherDataQueue")]string myQueueItem,

ILogger log)

{

messageProcessor.Process(myQueueItem);

log.LogInformation($"C# Queue trigger function processed: {myQueueItem}");

}

}

The Function class, in addition to logging, also processes the message using the MessageProcessor class.

Now that we have the Azure Function using an injected Dependency, we need to ensure that an instance of MessageProcessor is injected in via the constructor when the Azure Functions runtime executes the function.

Registering Services on Azure Functions Startup

If you are familiar with Dependency Injection in ASP NET Core applications, we use the Startup.cs class to register services into the ServiceCollection.

Similarly, in Azure Functions, we can create a Startup.cs class to register the dependencies. The name of the class is purely for consistency and can be different.

To set up the Startup class, we need to make sure,

- It inherits from

FunctionsStartupclass from the Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Extensions NuGet package. - Add an assembly directly to specify the class that acts as the Functions startup.

The below class is a sample Startup class that also registers the IMessageProcessor into the ServiceCollection used for Functions.

[assembly: FunctionsStartup(typeof(WeatherDataIngestor.Startup))]

namespace WeatherDataIngestor

{

public class Startup : FunctionsStartup

{

public override void Configure(IFunctionsHostBuilder builder)

{

builder.Services.AddTransient<IMessageProcessor, MessageProcessor>();

}

}

}

Run the application and drop a message to the Azure Queue to ensure it is picked up and processed correctly.

The Startup class runs once the Azure Functions host starts up and builds up the ServiceCollection used to resolve dependencies any time a new message is processed.

Configure Logging

The Run method in our Azure Function, ProcessWeatherDataFunction has the ILogger getting injected by the runtime. This is automatically done and is not using the ServiceCollection we set up in Startup.

However, we can inject an ILogger instance via the constructor using the ServiceCollection that we set up earlier. To do this, we need to move the ILogger to the constructor.

public ProcessWeatherDataFunction(

IMessageProcessor messageProcessor,

ILogger<ProcessWeatherDataFunction> log)

{

this.messageProcessor = messageProcessor;

this.log = log;

}

The above code injects in an instance of the ILogger<ProcessWeatherDataFunction> where the generic class type represents the category name used when logging.

To register logging related services, in the Startup class, invoke the AddLogging method as shown below.

public override void Configure(IFunctionsHostBuilder builder)

{

builder.Services.AddTransient<IMessageProcessor, MessageProcessor>();

builder.Services.AddLogging();

}

Understanding Azure Function Service Lifetimes

Depending on the lifetime used to register the services, each execution of Function gets the same or different instances of the dependencies.

As mentioned here, Azure Functions like ASP NET supports three service lifetimes

- Transient → New instance created every time an instance is requested

- Scoped → New instance is created once per function execution.

- Singleton → New instance created on host startup and reused for all function execution.

To understand this with an example, let’s create three separate classes to be used with different lifetimes. Below is a sample one for the Transient lifetime scope.

It has a Write method defined, which simply takes in a logger instance. A random Guide is set up in the class when it’s constructed. This is logged when the Write method is invoked.

The value of the Guide will help us determine if it’s the same instance or a new instance that gets injected into when an instance of this class is requested for.

public interface ITransientService

{

void Write(string message);

}

public class TransientService : ITransientService

{

private readonly ILogger<TransientService> logger;

public TransientService(ILogger<TransientService> logger)

{

Random = Guid.NewGuid().ToString();

this.logger = logger;

}

public string Random { get; }

public void Write(string message)

{

logger.LogInformation("Transient - {message}, {Random}", message, Random);

}

}

Similar to the above, I have also added the IScopedService and ISingletonService interface and associated implementations. It’s very similar to above except for a change in the message that’s logged.

Update the MessageProcessor class and use the Write method to log to the console. As shown below, the Process method calls the Write method of each lifetime-specific interface. It specifies the message as ‘Message Processor’ to indicate the source class it is getting used from.

public MessageProcessor(

ITransientService transientService,

ISingletonService singletonService,

IScopedService scopedService,

IOptions<MyConfigOptions> configOptions)

{

this.transientService = transientService;

this.singletonService = singletonService;

this.scopedService = scopedService;

this.configOptions = configOptions;

}

public void Process(string message)

{

if (message.Contains("exception"))

throw new Exception("Exception found in message");

transientService.Write("Message Processor");

scopedService.Write("Message Processor");

singletonService.Write("Message Processor");

}

To understand Lifetimes well, we need more dependencies that use these same services. This will help us understand how new dependencies are created when multiple instances of the dependency are requested from the DI container. Let’s add AnotherDependency to simulate this.

public class AnotherDependency : IAnotherDependency

{

private readonly ITransientService transientService;

private readonly ISingletonService singletonService;

private readonly IScopedService scopedService;

public AnotherDependency(

ITransientService transientService,

ISingletonService singletonService,

IScopedService scopedService)

{

this.transientService = transientService;

this.singletonService = singletonService;

this.scopedService = scopedService;

}

public void Process(string message)

{

transientService.Write("Another Dependency");

scopedService.Write("Another Dependency");

singletonService.Write("Another Dependency");

}

}

Update the Function class to take the AnotherDependency in the constructor.

public ProcessWeatherDataFunction(

IMessageProcessor messageProcessor,

IAnotherDependency anotherDependency,

ILogger<ProcessWeatherDataFunction> log)

{ ... }

[FunctionName("ProcessWeatherData")]

public void Run(

[QueueTrigger("add-weatherdata", Connection = "WeatherDataQueue")]string myQueueItem)

{

messageProcessor.Process(myQueueItem);

anotherDependency.Process(myQueueItem);

log.LogInformation($"C# Queue trigger function processed: {myQueueItem}");

}

With all the new dependencies wired up, let’s update the Startup class to wire up the new interfaces. Use the appropriate extension methods - AddTransient, AddScoped, AddSingleton - to register the new dependencies as shown below.

builder.Services.AddTransient<ITransientService, TransientService>();

builder.Services.AddScoped<IScopedService, ScopedService>();

builder.Services.AddSingleton<ISingletonService, SingletonService>();

builder.Services.AddTransient<IAnotherDependency, AnotherDependency>();

Run both applications. When the Azure Function host (console application running on the local machine) starts up, it will invoke the Startup class and register all dependencies. The methods in the Startup class are called only once.

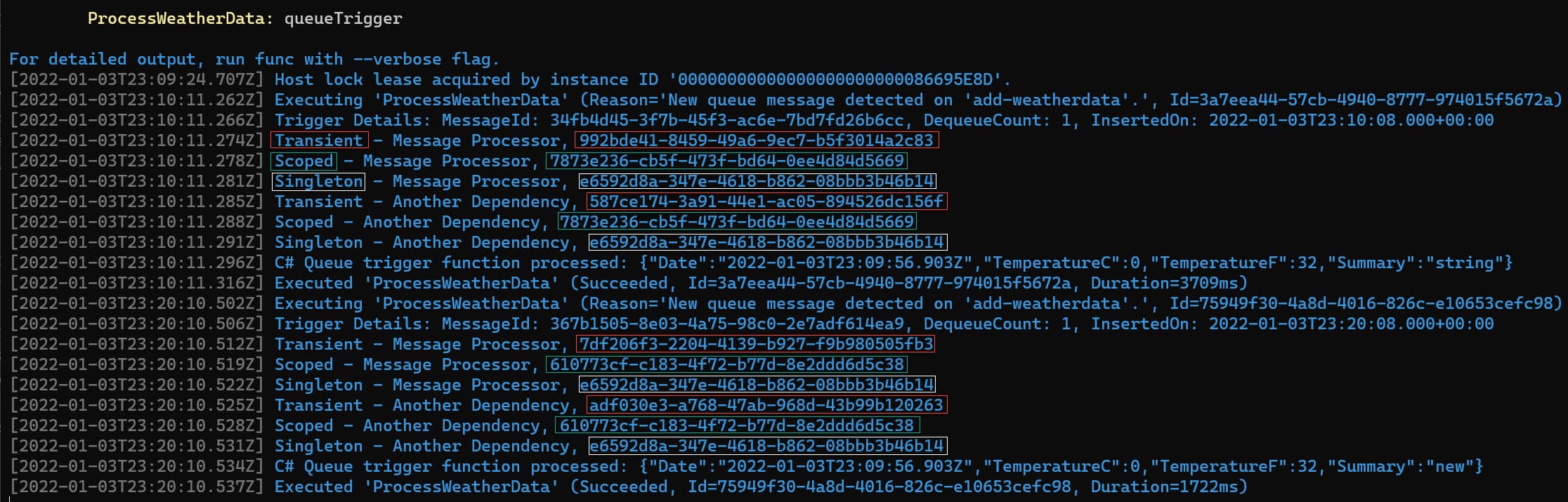

When a new message is dropped in the queue, and an instance of the Azure Function is created all the relevant dependencies are injected in. Below is a sample log output for two new messages processed.

The Transient Scoped service gets a different GUID for all instances. The GUID is the same for the Scoped one within the processing of a single message, so both MessageProcessor and AnotherDependency get the same instance. The instance is different for a different message since it gets a separate instance. For Singleton, the GUID is the same for all messages processed by the same host. In this case, our console app is the host.

App settings

By default, the template for Azure Functions does not support appsettings.json files. However, you can update the configuration to support configuration files.

To register different Configuration sources, we can override ConfigureAppConfiguration from the FunctionsStartup that we inherited from in our Startup class.

public override void ConfigureAppConfiguration(IFunctionsConfigurationBuilder builder)

{

base.ConfigureAppConfiguration(builder);

var context = builder.GetContext();

builder.ConfigurationBuilder

.AddJsonFile(

Path.Combine(context.ApplicationRootPath, "appsettings.json"),

optional: true, reloadOnChange: false)

.AddJsonFile(

Path.Combine(context.ApplicationRootPath, $"appsettings.{context.EnvironmentName}.json"),

optional: true, reloadOnChange: false)

.AddEnvironmentVariables();

}

The above override sets up the ConfigurationBuilder to use the appsettings.json and environment-specific appsettings file. You can also update this to use other Configuration Source Providers available in .NET. If you want to learn more about Configuration, check out the video below.

Once set up, we can also use Options Pattern within our Azure Functions. We can create a custom class to represent the config data, and dependency inject into our Function classes and dependencies for a configuration like below.

{

"MyConfig": {

"Url": "http://testapi.com",

"Secret": ""

}

}

The code below in the Startup class, wires up the class MyConfigOptions into the Service Collection and makes it available to be dependency injected as shown below in MessageProcessor as IOptions<MyConfigOptions>

public class MyConfigOptions

{

public string Url { get; set; }

public string Secret { get; set; }

}

...

builder.Services.AddOptions<MyConfigOptions>()

.Configure<IConfiguration>((settings, configuration) =>

{

configuration.GetSection("MyConfig").Bind(settings);

});

...

public MessageProcessor(IOptions<MyConfigOptions> configOptions) {...}

Azure Functions by default also supports Secrets Manager if you want to store sensitive information on local development environment machines. You can right-click (in Visual Studio) on the project, enable ‘Manage User Secrets’ in the menu, and set the sensitive configuration in the secrets.json file.

I hope this helps you understand how Dependency Injection can be used when building Azure Functions and the different use cases.

Rahul Nath Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.